At what point do BBC ‘correspondents’ cross the line from offering a properly judged and impartial assessment into propaganda and overt electioneering?

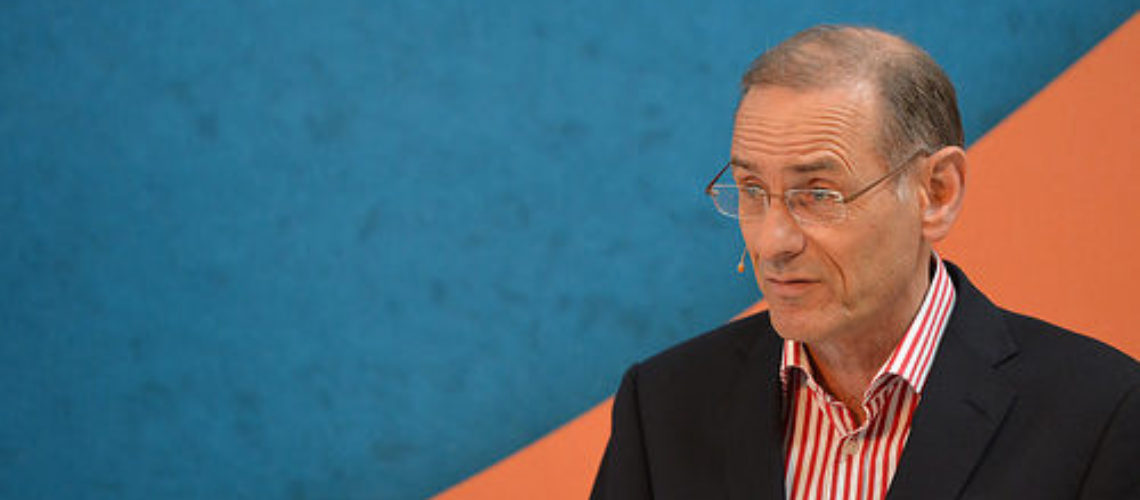

News-watch surveys provide abundant evidence that it is all too often – and a new prime example was 556 words on the doctrine of climate alarmism from Roger Harrabin the BBC’s ‘environment analyst’ on Radio 4’s The World This Weekend yesterday. (His report starts at a round 1.25pm)

This amounted to a BBC party political broadcast against elements of the Conservative party, and especially – to Harrabin – the real villains of the piece, Ukip.

A transcript of the full horror of what he delivered in this ‘impartial assessment’ is below.

Where to start? In Harrabin’s world, our seas are ‘full of plastic’ (!), and the fact that Stephen Hawking thinks that climate change is the biggest long-term threat to humanity makes his speculation sacrosanct.

Then we must take into account that, according to government surveys, only 1% ‘strongly oppose renewables’ and so that, in Harrabin’s world, makes the spending of billions on such energy (instead of, say, the NHS) OK.

No mention in his equation of the thousands of old people who freeze in winter because of the huge bills generated by wind farm and solar subsidies.

And who, according to Harrabin, are the irresponsible and reckless parties who are opposing the climate alarmism agenda? Top if his list are ‘Conservative libertarians’, followed by – boo, hiss! – Ukip. Of course! Every BBC correspondent’s favourite whipping boys. Along with Donald Trump, who also dares to question this sacred dogma.

Next on the list of Harrabin infamy is The Mail on Sunday, which had the temerity to launch its Great Green Con campaign and thereby ‘legitimised’ anti-environmentalism’. How very dare they.

Next target? Brexit – this is the BBC so how could another aspect of related problems be avoided? , Now at risk is all the wonderful legislation emanating from Brussels designed to ‘restore nature’ (whatever that means). As a result ,too, of leaving the EU at risk will be flood control, along with the drive to spend billions on insulating millions of homes.

Harrabin concludes – with outrageous partiality – during an election campaign:

The Conservatives’ ambition looks limited here compared with the Lib Dems, Greens and Plaid Cymru and also Labour who want to make home insulation an infrastructure priority. The SNP hasn’t published its manifesto yet but it too wants to take a strong line on climate change.

So there we have it. Vote anything but Conservative and Ukip, and avoid Brexit and all will be well with the world. Humanity will be safe.

Transcript of BBC Radio 4, ‘The World This Weekend’, 28 May, 2017, Climate Change, 1.27pm

MARK MARDELL: And as one Carlisle resident said, there hasn’t been much about the environment generally, even though it was once near the top of many a politician’s agenda. What happened? Here’s our environment analyst Roger Harrabin.

ROGER HARRABIN: Air pollution, melting sea ice, wildlife depletion, a soil crisis, seas full of plastic. Why isn’t the election full of environmental angst? Well I think it’s mainly a question of worry capacity. Stephen Hawking would tell you climate change was the biggest long-term threat to humanity but in the meantime we’re also beset by terrorism, the refugee crisis, Brexit – they’ve filled up our worry-space. Coupled with that there’s been a shift in the way the media discusses the environment. The old consensus on climate change has been rattled by a long campaign from Conservative libertarians and UKIP. They scored their first success with wind farms, scattered protests against turbines were at first below the radar of the national media, but those angry local voices were eventually amplified by the Telegraph, and that began to influence policy. The government’s own surveys actually suggest that just 1% of the populace strongly opposes renewables, but that’s by the by. Then the Mail on Sunday launched its Great Green Con campaign criticising failings in renewables and highlighting uncertainties in climate science. When it was previously non-PC to declare yourself a climate change sceptic, a stance of what you might call anti-environmentalism has now been legitimised. This steady pressure from over its right shoulder has led the government to mostly gag itself on climate change over recent years and the sceptics have been claiming victory. But wait a minute – except UKIP, all the manifestos published so far, that’s including the blue one, recommit to the Climate Change Act. That sort of consensus hardly stimulates media interest, but it does prove the issue hasn’t gone away. There are details over policy of course. The Conservative manifesto aspires to the cheapest energy prices in Europe. The Greens promise affordable energy, not cheap energy. But as a slogan that’s not quite so catchy. For all parties Brexit looms large, 80 % of the UK’s environmental policy comes through the EU. How will politicians translate that into UK law? How will they handle the massive opportunity to restore nature as they’ve promised following British withdraw from the common agriculture policy? Can they direct some of the agricultural budget to catching water on farmland to prevent the floods we discussed earlier? How will they improve the chaotic waste and recycling policies and how will our next government solve the conundrum of persuading tens of millions of people to insulate their own homes as part of the supposedly inexorable drive towards the low carbon economy? The Conservatives’ ambition looks limited here compared with the Lib Dems, Greens and Plaid Cymru and also Labour who want to make home insulation an infrastructure priority. The SNP hasn’t published its manifesto yet but it too wants to take a strong line on climate change. Then how will the parties deal with the thorny issue of air pollution? Policies are there in other manifestos but details are strikingly absent from the Conservative document, presumably to avoid upsetting diesel drivers. So many environmental questions still, so many unanswered.